After three years of civil war, Ulysses S. Grant found himself confronting Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia for the first time in a clash that would become known as the Battle of the Wilderness. Grant was the latest of a long line of Union Generals to command the Army of the Potomac, and after a near disastrous second day of battle – one of the bloodiest of the war – Grant’s future looked as ominous as those of the failed Union Generals’ before him.

May 7, 1864

“In plain fact, up to the point of obliging Grant to throw in the sponge and pull back across the river, Lee had never beaten an adversary so soundly as he had beaten this one in the course of the past two days. What it all boiled down to was that Grant was whipped, and soundly whipped, if he would only admit it by retreating which in turn was only a way of saying that he had not been whipped at all. ‘Whatever happens, there will be no turning back,’ he had said, and he would hold to that. The mid afternoon displacement of the guns deployed along the Union line of battle was in preparation for a march, just as the troops assumed, but not in the direction they supposed.” “The objective was Spotsylvania Courthouse, less than a dozen miles down the Brock Road from the turnpike intersection.”

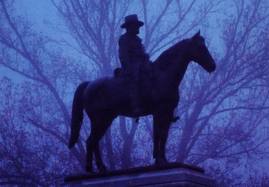

“Soon after dark the expected orders came; Warren’s and Sedgwick’s veterans slung their packs, fell in quietly on the Brock Road and the turnpike, and set out. To the surprise of V Corps men, the march was south, in rear of Hancock’s portion of the line. At first they thought that this was done to get them onto the plank road, leading east to Chancellorsville, but when they slogged past the intersection they knew that what they were headed for was not the Rapidan or the Rappahannock, but another battle somewhere south, beyond the unsuspecting rebel flank. Formerly glum, the column now began to buzz with talk. Packs were lighter; the step quickened; spirits rose with the growing realization that they were stealing another march on old man Lee. Then came cheers, as a group on horseback – ‘Give way, give way to the right,’ one of the riders kept calling to the soldiers on the road – doubled the column at a fast walk, equipment jingling. In the lead was Grant, a vague, stoop-shouldered figure, undersized-looking on Cincinnati, the largest of his mounts; the other horsemen were his staff. Cincinnati pranced and sidled, tossing his head at the sudden cheering, and the general, who had his hands full getting the big animal quieted down, told his companions to pass the word for the cheers to stop, lest they give the movement away to the Confederates sleeping behind their breastworks in the woods half a mile to the west. The cheering stopped, but not the buzz of excitement, the elation men felt at seeing their commander take the lead in an advance they had supposed was a retreat. They stepped out smartly; Todd’s Tavern was just ahead, a little beyond the midway point on the march to Spotsylvania.

Up on the turnpike, where Sedgwick’s troops were marching, the glad reaction was delayed until the head of the column had covered the gloomy half dozen miles to Chancellorsville. ‘The men seemed aged,’ a cannoneer noted as he watched them slog past a roadside artillery park. Weary from two days of savage fighting and two nights of practically no sleep, dejected by the notion that they were adding still another to the long list of retreats the army had made in the past three years, they plodded heavy-footed and heavy-hearted, scuffling their shoes in the dust on the pike leading eastward. Beyond Chancellorsville, just ahead, the road forked. A turn to the left, which they expected, meant re-crossing the river at Ely’s Ford, probably to undergo another reorganization under another new commander who would lead them, in the fullness of time, into another battle that would end in another retreat; that was the all-too-familiar pattern, so endless in repetition that at times it seemed a full account of the army’s activities in the Old Dominion could be spanned in four short words, ‘Bull Run: da capo.’ But now a murmur, swelling rapidly to a chatter, began to move back down the column from its head, and presently each man could see for himself that the turn, beyond the ruins of the Chancellor mansion, had been to the right. They were headed south, not north; they were advancing, not retreating; Grant was giving them another go at Lee. And though on sober second thought a man might be of at least two minds about this, as a welcome or a dread thing to be facing, the immediate reaction was elation. There were cheers and even a few tossed caps, and long afterwards men were to say that, for them, this had been the high point of the war. ‘Our Spirits rose,’ one among them would recall. ‘We marched free. The men began to sing…That night we were happy.’ ‘Ulysses,’ another soldier said, ‘don’t scare worth a damn.’ ” The Civil War by Shelby Foote

You must be logged in to post a comment.